Summary

We tend to remember the good, or the illusions of good, and drown out the negative.

In the 1970s, Hollywood didn’t just tell love stories about teenagers—it crafted narratives that shaped cultural perceptions of adolescence as a shared, idealized experience, influencing how audiences viewed youth as a national identity, a fashion statement, and a mythic origin.

Teen romance movies existed long before the 1970s, but the decade changed what they meant. The 1950s helped Hollywood recognize teenagers as a distinct moviegoing audience, accelerating what scholars describe as a broader “juvenilization” of American cinema—films designed to speak directly to youth tastes and anxieties.

In the 1960s, the genre splintered: beach-party fantasies sold “good clean fun” and insulated escapism, while late-decade youth-culture films began drawing young viewers in record numbers—especially as the MPAA ratings system arrived in 1968 and loosened the old rulebook by categorizing content rather than prescribing it.

Then the 1970s pulled a neat trick: instead of focusing on “what teen romance is now,” it asked what teen romance is when you look back. And it answered with two defining myths—the last night of innocence and high school as musical heaven—made iconic by American Graffiti (1973) and Grease (1978). This creates a sense of shared cultural belonging, inviting the audience to feel part of a collective memory.

The 1970s didn’t recreate the teenage past. It stylized it—then handed it back as a myth audiences could sing, cruise, and replay-creating a comforting sense of coherence and familiarity that appeals to viewers’ nostalgia.

Act I: The Past Becomes a Product

To understand why the 1970s leaned so hard into nostalgia, you must see how quickly the late 1960s rewired Hollywood economics and tone. Britannica describes 1967–69 as a turning point when major films drew youth audiences to theaters in record numbers, and notes that the 1968 MPAA ratings system enabled “new permissiveness toward sex” by replacing the Production Code’s prescriptions with age-based categories. That shift didn’t just expand what could be shown—it expanded what could be sold: youth stories could now be more adult in tone and more youth-targeted in marketing.

At the same time, the teen film was becoming less a single genre than a portable storytelling engine—capable of blending romance with comedy, drama, music, and social observation. Academic work on the teen film emphasizes that the category encompasses multiple subgenres and hybrids, and that teen films often appear in cycles—breakout hits followed by waves of imitators. The 1970s nostalgia cycle worked the same way, except the “trend” wasn’t just a plot type—it was a feeling: the belief that the recent past was more coherent, more legible, more shareable than the present.

Act II: Myth #1 — “The Last Night of Innocence” (American Graffiti)

Videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19LNS00xh80

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dfhYdoVQSJA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUHe0jgtsY4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhsQSEOiPok

American Graffiti is nostalgia with a pulse. Set in 1962, it follows teenagers through a single night of cruising and flirting, thereby creating a myth that shapes how audiences perceive adolescence as a fleeting yet memorable experience.

The romance in American Graffiti is not the glossy “one true couple” arc that later teen rom-coms would normalize. Instead, it employs myth-making techniques like capturing fleeting moments, chance encounters, crushes that flare and fade, conversations that feel important because they happen at night, in cars, with the radio humming, to create a nostalgic ideal of adolescence as a mural rather than a morality tale, engaging viewers with its mythic quality.

What makes the movie feel like a memory isn’t only the setting—it’s the soundtrack logic. Britannica notes that Lucas originally envisioned even more rock-and-roll hits. He had to narrow the list, underscoring how central music reproduction costs and song selection were to the film’s identity. The songs do the work memory does: they compress time, summon emotion, and make personal experience feel universal.

In American Graffiti, teen romance isn’t a destination. It’s a passing headlight—proof that you were young, moving, and already leaving.

Act III: Myth #2 — “High School as Musical Heaven” (Grease)

Videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=drdM5dOkOtM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQB_QvXMWXY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYk0_U7kf3g&list=RDRYk0_U7kf3g&start_radio=1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=jzPygnkUTf4

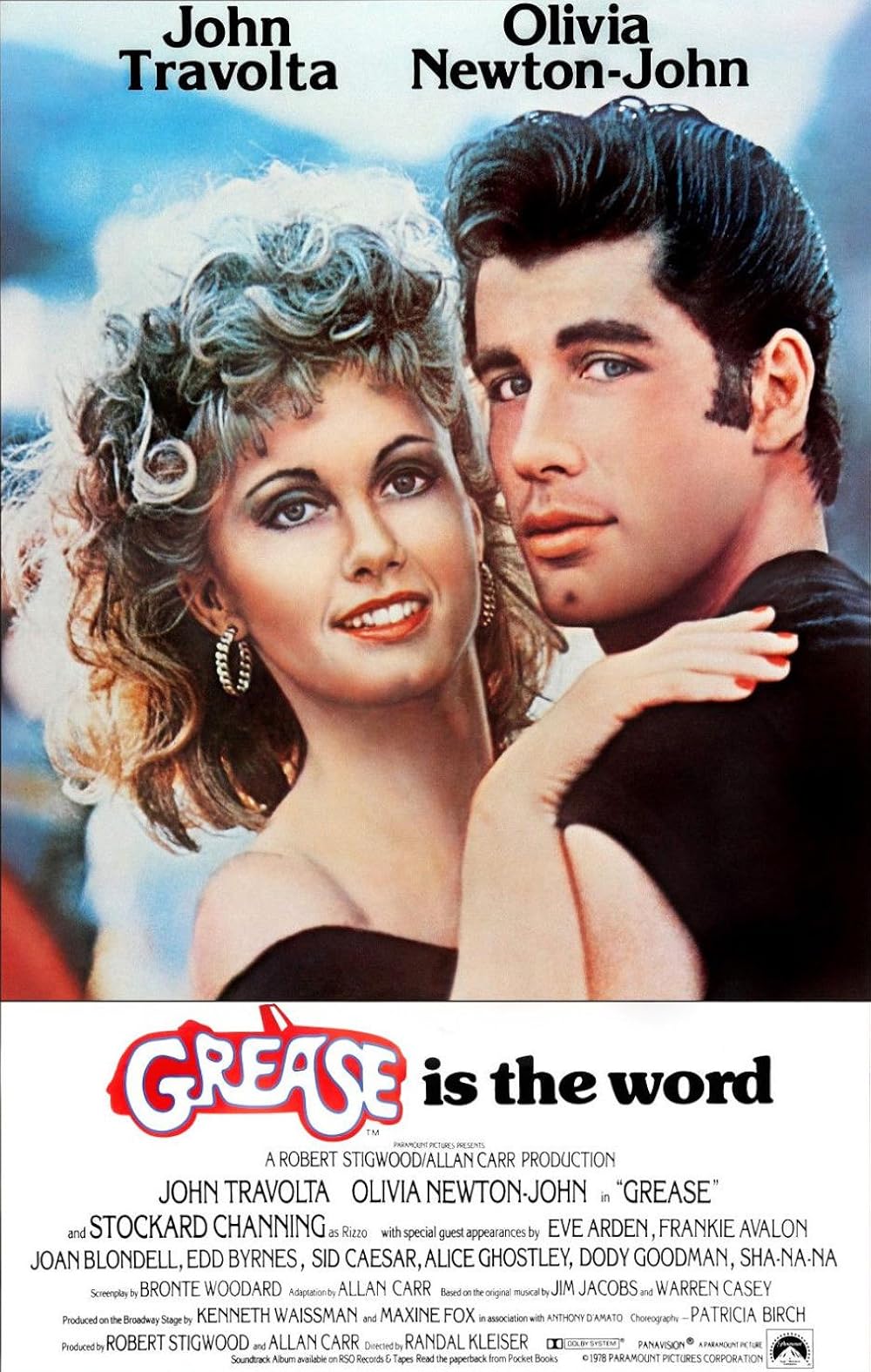

If American Graffiti mythologizes adolescence as bittersweet realism, Grease mythologizes it as pop operetta. Released in 1978, set in 1958, and adapted from a Broadway musical, the film follows the romance between Danny Zuko and Sandy Olsson, staging high school as a world in which identity is performed, tested, and revised through music. Its scale and staying power are part of the myth: it became the highest-grossing musical film of its time, and it was later selected for preservation in the National Film Registry, an institutional recognition of its cultural significance.

What’s crucial is that Grease doesn’t try to reproduce the 1950s accurately—it tries to produce a version of the 1950s that feels like a shared fantasy. Britannica highlights how the title song blends Frankie Valli’s doo-wop crooning with a “funky 1970s beat,” a sonic confession that this is the past filtered through the present’s pop sensibility. That blend—1950s imagery + 1970s energy—is the key to 70s nostalgia: it allows audiences to feel they’re remembering a past while actually consuming a newly manufactured one.

Music and group rituals in Grease foster a sense of belonging, making viewers feel part of a shared cultural experience that reinforces nostalgia.

Grease doesn’t remember high school. It redesigns high school—then dares you not to believe it.

Why the 1970s Nostalgia Wave Worked: Three Myth Tools

1) Music as a time machine

Both films use music as a shortcut to meaning: American Graffiti embeds early rock-and-roll hits into cruising culture. At the same time, Grease turns romance into choruses and refrains, making feeling singable—and therefore repeatable. This repeatability taps into nostalgia’s myth-making power, emphasizing ‘firsts'-first crush, first humiliation-that create a shared emotional memory, reinforcing the cultural significance of teen romance as a universal, mythic experience.

2) Iconic spaces as ritual sites

The strip, the diner, the gym, the school dance—these become sacred spaces of youth mythology. American Graffiti makes the street itself the stage; Grease makes the school campus the theater. Once teen romance is tied to ritual spaces, it becomes easy for later generations to adopt it as a template—because you can recreate the setting even when the decade changes.

3) Innocence as legibility

Mid-1960s beach movies sold an explicit fantasy where “virginity prevails,” and social upheaval never intrudes; they were “complete fantasy,” designed to be frictionless. The 1970s nostalgia wave is subtler: it doesn’t say the past was morally perfect; it says the past was understandable—with clearer roles, clearer rituals, clearer soundtracks. That’s the heart of myth-making: not truth, but coherence.

Nostalgia doesn’t claim the past was better. It claims the past was legible—and teen romance loves anything legible.

What the 1970s Changed in the Long Run

The most important legacy of 1970s teen-romance nostalgia is that it created a reusable cultural machine: set a story slightly “back,” load it with music cues, anchor it to ritual spaces, and let romance stand in for an entire way of life. Later decades would return teen romance to the present tense (especially in the 1980s boom), but the “myth template” remained: soundtracks as identity, cliques as symbols, high school as a miniature society, first love as a generational marker.

And institutional memory now confirms the magnitude. Grease’s National Film Registry selection (and American Graffiti’s canon status as a formative coming-of-age hit) signals that these weren’t just popular films—they became part of America’s curated film heritage. In other words, the 1970s didn’t merely entertain teenagers; it taught the culture how to remember being one.

The 1970s taught Hollywood that teen romance could carry an entire era on its shoulders—if you gave it the right song.

“Two Kinds of 1970s Teen-Romance Nostalgia”

-

Bittersweet time capsule: American Graffiti — youth as motion, music, and goodbye.

-

Pop mythology: Grease — youth as performance, reinvention, and chorus.