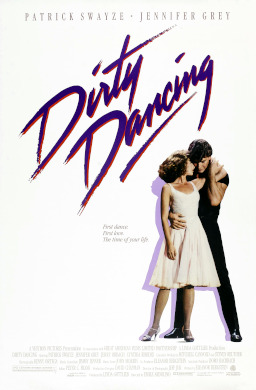

In pop culture, Dirty Dancing is often reduced to one perfect moment: the final dance, the soaring lift, the line that refuses to sideline a young woman. But the film’s true significance lies in its ability to embed class conflict, sexual politics, and bodily autonomy into what appears—at first glance—to be a sun-drenched summer romance, thereby deepening its social and artistic Impact.

It’s not just a dance movie. It’s a coming-of-age story that makes freedom visible—one step, one choice, one risk at a time.

Videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WpmILPAcRQo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47DLiBH9WMY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XINddkzfTzM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciwbLr3n9Ic

A Summer in 1963—Before the World (and Baby) Changes

Set during the summer of 1963 at a resort in the Catskills/Borscht Belt, Dirty Dancing follows Frances “Baby” Houseman (Jennifer Grey), the idealistic daughter of a doctor, as her family vacations at Kellerman’s. She drifts from the polite rituals of the guests into the staff’s after-hours world—where music is louder, bodies move closer, and the rules are written by rhythm rather than respectability.

Baby’s entry point isn’t rebellion for rebellion’s sake; it’s empathy. When she learns that Penny (Cynthia Rhodes), a dancer, is in crisis, Baby volunteers to help—an act that pulls her into Penny’s orbit and into the arms (and instruction) of Johnny Castle (Patrick Swayze), the resort’s dance instructor. The love story begins there, but the film’s deeper themes do, too: who gets protected, who gets judged, and who gets blamed.

Kellerman’s is a miniature society with strict borders that mirror real social divides. Baby’s crossing of class lines highlights the film’s exploration of social tension and empathy, emphasizing its cultural importance.

Kellerman’s functions as a microcosm of society, where class boundaries generate tension that drives the film’s narrative and themes.

Johnny is competent and charismatic, yet is constantly reminded that he is replaceable labor. Baby is curious, sheltered, and continuously reminded she is protected. Their relationship isn’t merely “forbidden love”; it’s a collision between economic realities: she can take risks and still be caught by a safety net, while he cannot. That imbalance gives the romance its electricity—and its moral seriousness.

The movie’s heat comes from chemistry; its weight comes from class.

The Plot Twist That Isn’t a Twist: Reproductive Autonomy at the Center

Here’s the truth that rewires the film: Dirty Dancing’s entire plot depends on an illegal abortion storyline. It’s not an “issue subplot” bolted on for gravitas; it’s the hinge that forces Baby to step into Penny’s place as Johnny’s dance partner, which in turn creates the intimacy that becomes love.

WETA/PBS put it bluntly: the film “wouldn’t be possible” without the abortion at its heart. And Eleanor Bergstein, the screenwriter and co-producer, has described real pushback to remove it—precisely why she embedded it so deeply into the story that it couldn’t be cut without collapsing the narrative.

The most radical thing about Dirty Dancing isn’t how close the dancers get. It’s that the film insists consequences belong in the same frame as desire.

The romance is the surface. The abortion storyline is the structure.

Dance as Language: How Movement Becomes Self-Respect

Because the film is about bodies—who control them, who profits from them, who shames them—dance becomes more than performance. It becomes speech. Baby begins the story as a watcher, a good daughter, a “nice girl.” By the end, she has learned that being “nice” is not the same as being free.

Johnny doesn’t “save” Baby; he invites her to take space—socially, emotionally, physically. The final performance is remembered for its lift, which suggests transcendence. But what it signifies is grounded and practical: Baby walks into the center of the room as if she has earned her own authority.

Takeaway: The dancing isn’t decoration; it’s character development.

The Soundtrack as a Second Script

If the film teaches you to see dance as language, its soundtrack functions like a second screenplay—telegraphing mood, desire, and transformation at a near-primitive level. The movie’s music became a phenomenon in its own right: Wikipedia notes that the soundtrack (produced by Jimmy Ienner) generated multi-platinum albums and multiple hit singles.

And then there’s the closer: “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life.” The song won the Academy Award for Best Original Song, the Golden Globe for Best Original Song, and a Grammy for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals—an awards sweep that explains why the final scene lives in collective memory like a shared dream.

Some movies end with credits. This one ends with an anthem—and dares you not to feel it.

The soundtrack didn’t support the movie; it helped immortalize it.

A Low-Budget Hit That Became a Cultural Institution

Part of Dirty Dancing’s legend is how disproportionate its success was to its scale. The film was made on a modest budget (reported at $4.5 million) and went on to earn about $214 million worldwide—numbers that reflect not just popularity, but replay value.

The staying power has now been stamped into official cultural memory: in December 2024, the Library of Congress added Dirty Dancing to the National Film Registry, citing its artistic, historic, or aesthetic significance. That recognition matters because it confirms what audiences have long practiced: revisiting the film isn’t only nostalgia—it’s participation in a shared American artifact.

It’s a crowd-pleaser with archival credentials.

Place Matters: The Look of Memory

Although the story is set in the Catskills, production took place in Lake Lure, North Carolina, and Mountain Lake, Virginia, locations whose natural beauty helps the film feel like a remembered summer—warm at the edges, vivid at the center. The scenery does more than supply postcard charm; it reinforces the film’s central tension between curated leisure and the labor behind it.

Why Dirty Dancing Still Hits

The movie survives because it satisfies on multiple levels at once:

- As romance, it delivers yearning, danger, and tenderness without apology.

- The movie endures because it satisfies on multiple levels: as a romance with genuine yearning and tenderness, and as a social story that vividly stages class divides and workplace vulnerability within a setting that remains deceptively innocent, cementing its cultural significance.

- As political memory: it insists the pre–Roe reality of illegal abortion is not ancient History—it’s lived experience worth remembering.

- As a pop ritual, it ends with music and movement so iconic that they have become cultural shorthand for liberation.

What keeps audiences returning isn’t only chemistry or the choreography. It’s the sensation that a young woman learns, in public, to stop asking permission to occupy her own life.

The lift is famous because it looks like a flight, but the movie’s real triumph is that Baby learns how to stand.