Few songs capture the ache of longing as powerfully as Roy Orbison’s 1963 classic, “In Dreams.” Framed as a nocturnal journey where love briefly returns, the song suspends reality long enough to offer solace before daylight breaks the spell. Orbison’s singular voice—operatic, intimate, and unguarded—turns this brief escape into a meditation on desire and impermanence. Understanding “In Dreams” means situating it within the arc of Orbison’s career: from early rockabilly experiments at Sun Records to the emotionally rich ballads of his Monument era, and later, a renaissance through cultural reappraisal in the 1980s. Along the way, the song’s structure, symbolism, and Impact reveal why it continues to haunt listeners across generations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9mD_mIsEPKQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-8Jz3VW7rYk

Crying: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4uNoAp7RNUA&list=RD4uNoAp7RNUA&start_radio=1

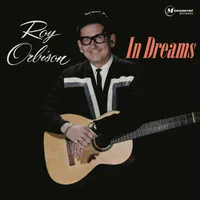

The Artist Behind the Ballad

By the early 1960s, Orbison had transitioned from Sun Records—where he found modest success with “Ooby Dooby”—to Monument Records, which encouraged his shift toward grand, orchestrated ballads like “Only the Lonely,” “Running Scared,” and “Crying.” This period showcased his wide vocal range and a willingness to foreground vulnerability, a departure from the cocky posture typical of male rock performers at the time. His music became synonymous with emotional candor and complex textures that underscored romantic anxiety and yearning.

A Song Built Like a Dream

Released in February 1963, “In Dreams” stands out for its through-composed design—seven distinct musical movements without a repeated chorus. For music students and critics, its progression as A–B–C–D–E–F–G, each section escalating emotion and texture, showcases innovative songwriting that amplifies the song’s Impact and structural uniqueness among early rock singles.

Symbolism: Dreams as Sanctuary and Mirage

In Orbison’s narrative world, dreams function as a sanctuary—a private realm where the beloved returns and conversation resumes without the constraints of reality. For cultural critics and fans, this dual symbolism encapsulates the tension between idealism and acceptance: we yearn for the impossible, and even our most comforting illusions carry the seed of heartbreak, prompting reflection on human longing and impermanence.

Performance Persona and Emotional Truth

Orbison’s public image—dark attire, minimal motion, and trademark sunglasses—reinforced the inward focus of his music. To critics and scholars, this vulnerability invites empathy, emphasizing how his quiet stage presence and powerful upper register allowed audiences to connect emotionally without sentimentality, turning private grief into communal catharsis.

Cultural Afterlife: From The Beatles’ Era to Blue Velvet

“In Dreams” initially climbed to #7 on the Billboard Hot 100 and spent months on UK charts while Orbison toured with The Beatles, a testament to its appeal in a rapidly changing musical landscape. Decades later, David Lynch’s use of the song in 1986’s Blue Velvet introduced Orbison to a new generation, catalyzing a late-career resurgence and inspiring him to re-record his classics for In Dreams: The Greatest Hits. The film’s unsettling, dreamlike framing dovetailed with the song’s themes, reaffirming its relevance and emotional potency. Rolling Stone would later enshrine “In Dreams” among the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, a testament to its enduring artistic stature.

Conclusion

Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” is more than a ballad—it’s a timeless reflection on the human condition. Through its operatic structure and haunting vocal delivery, Orbison transforms a straightforward narrative of lost love into a profound meditation on longing and impermanence. Dreams, in his vision, are both sanctuary and illusion: they offer solace from heartbreak yet dissolve with the dawn, leaving us to confront reality’s harsh truths. This duality resonates because it mirrors our own struggles—the tension between what we desire and what life allows. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to articulate universal feelings of hope, loss, and the fleeting nature of happiness, ensuring its relevance across generations.

Orbison’s ability to channel vulnerability into art set him apart in an era dominated by bravado. His music gave voice to emotions often left unspoken, and “In Dreams” stands as a pinnacle of that gift. Decades later, its inclusion in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet reaffirmed its cultural power, proving that its themes of hope and fragility remain universal. In the end, Orbison reminds us that while dreams may vanish, their beauty—and the yearning they represent—endures in memory and music. That is why “In Dreams” continues to echo across generations: it speaks to the deepest corners of the heart, where love and loss are inseparable.