Summary:

When Harper Lee published To Kill a Mockingbird in 1960, America was on the cusp of monumental social change. The Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum, challenging segregation and systemic racism entrenched in Southern life. Against this backdrop, Lee’s novel offered a piercing critique of prejudice through the eyes of a child, Scout Finch, and her father, Atticus—a lawyer who defends a Black man falsely accused of raping a white woman. The book’s moral clarity and call for empathy resonated deeply with readers confronting the realities of Jim Crow laws and racial violence.

Article:

1960s: A Mirror for a Nation in Transition

In the early 1960s, the novel served as both a reflection and a provocation. It mirrored the injustice African Americans faced daily and provoked readers to question their own complicity in a system built on inequality. Atticus Finch became an emblem of moral courage, inspiring those who sought justice during a time when standing against the status quo carried real risk. Schools embraced the book not just as a story but as a powerful tool for social awareness, and its popularity helped normalize conversations about race and fairness in mainstream culture.

Today: A Story That Still Speaks

More than six decades later, To Kill a Mockingbird remains culturally significant—but for new reasons as well as old. Racial inequities persist in policing, housing, and the courts, making Tom Robinson’s trial feel hauntingly familiar. The novel’s powerful plea for empathy—“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view”—is urgent in an era marked by political polarization and social fragmentation. Atticus Finch continues to symbolize ethical leadership, though modern readers also critique the book’s limitations, such as its “white savior” framing. These discussions underscore its evolving role: not just as a classic, but as a springboard for deeper dialogue about justice and representation.

Why It Endures

Ultimately, the story endures because its themes are universal: the struggle between fairness and prejudice, the loss of innocence, and the moral imperative to stand for what is right. Whether in the 1960s or today, To Kill a Mockingbird challenges readers to confront uncomfortable truths—and to imagine a society where empathy triumphs over fear.

To Kill a Mockingbird: Cultural Significance Then and Now

When Harper Lee published To Kill a Mockingbird in 1960, America was on the cusp of monumental social change. The Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum, challenging segregation and systemic racism entrenched in Southern life. Against this backdrop, Lee’s novel offered a piercing critique of prejudice through the eyes of a child, Scout Finch, and her father, Atticus, a lawyer who defends a Black man falsely accused of raping a white woman. The book’s moral clarity and call for empathy resonated deeply with readers confronting the realities of Jim Crow laws and racial violence.

1960s: A Mirror for a Nation in Transition

In the early 1960s, the novel served as both a reflection and a provocation. It mirrored the injustice African Americans faced daily and provoked readers to question their own complicity in a system built on inequality. Atticus Finch became an emblem of moral courage, inspiring those who sought justice during a time when standing against the status quo carried real risk. Schools embraced the book as a tool for social awareness, and its popularity helped normalize conversations about race and fairness in mainstream culture.

Today: A Story That Still Speaks

More than six decades later, To Kill a Mockingbird remains culturally significant—but for new reasons as well as old. Racial inequities persist in policing, housing, and the courts, making Tom Robinson’s trial feel hauntingly familiar. The novel’s plea for empathy—“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view”—is urgent in an era marked by political polarization and social fragmentation. Atticus Finch continues to symbolize ethical leadership, though modern readers also critique the book’s limitations, such as its “white savior” framing. These discussions underscore its evolving role: not just as a classic, but as a springboard for deeper dialogue about justice and representation.

Why It Endures

Ultimately, the story endures because its themes are universal: the struggle between fairness and prejudice, the loss of innocence, and the moral imperative to stand for what is right. Whether in the 1960s or today, To Kill a Mockingbird challenges readers to confront uncomfortable truths—and to imagine a society where empathy triumphs over fear.

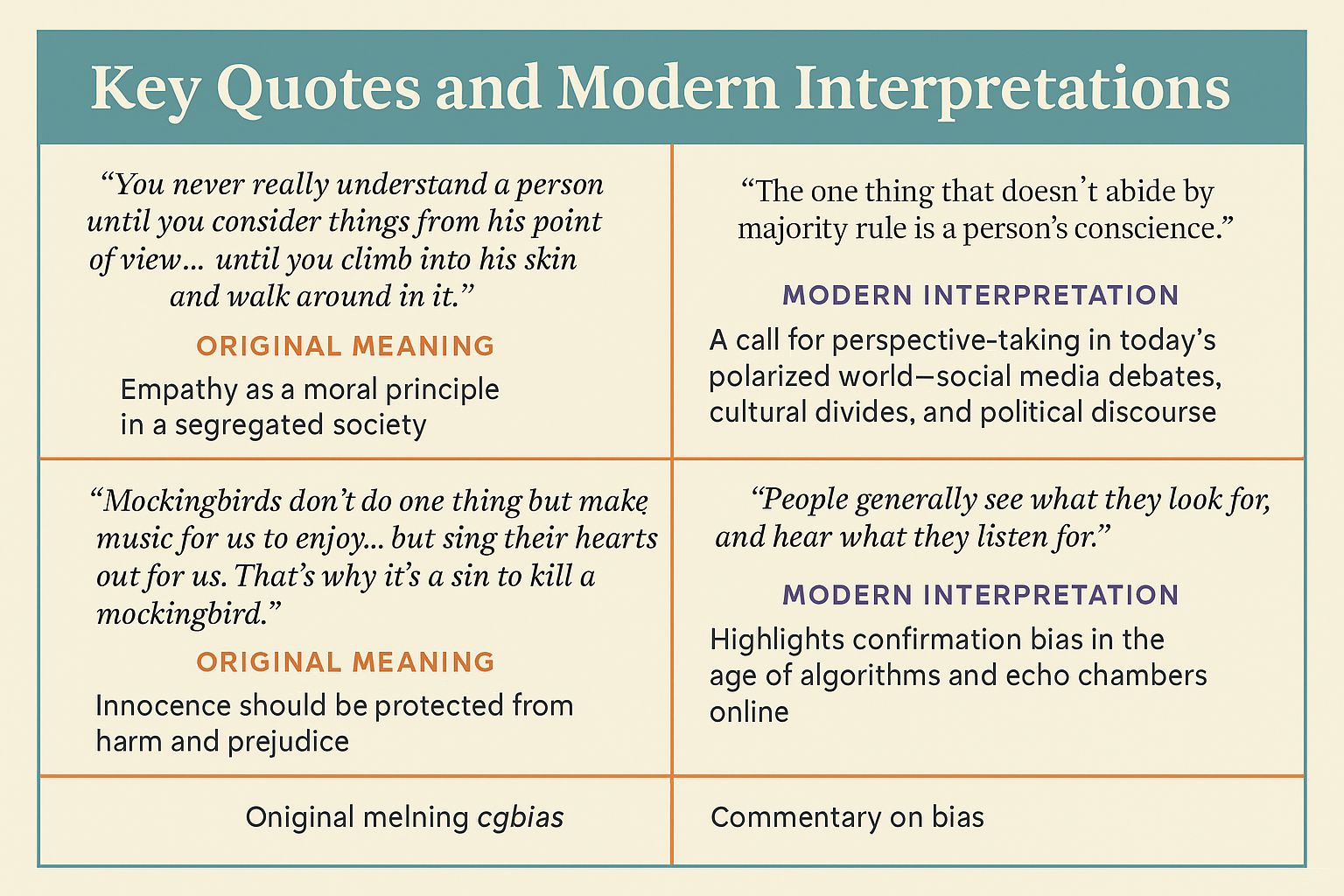

Key Quotes and Modern Interpretations

|

Quote |

Original Meaning |

Modern Interpretation |

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” |

Empathy as a moral principle in a segregated society. |

A call for perspective-taking in today’s polarized world—social media debates, cultural divides, and political discourse. |

“The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience.” |

Individual morality should guide action, even against popular opinion. |

Relevant in discussions about whistleblowing, ethical leadership, and resisting groupthink in modern institutions. |

“Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy… but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” |

Innocence should be protected from harm and prejudice. |

Symbolic of safeguarding vulnerable groups—immigrants, minorities, and marginalized voices in today’s society. |

“People generally see what they look for, and hear what they listen to.” |

Commentary on bias and selective perception. |

Highlights confirmation bias in the age of algorithms and echo chambers online. |